In Conversation with Gavin Benjamin

Erica Nuckles (EN): I started in my role here the same week you started thinking about this project, and Jeremiah has recently joined the Museum, so perhaps we can start with how the idea for this series first came to you?

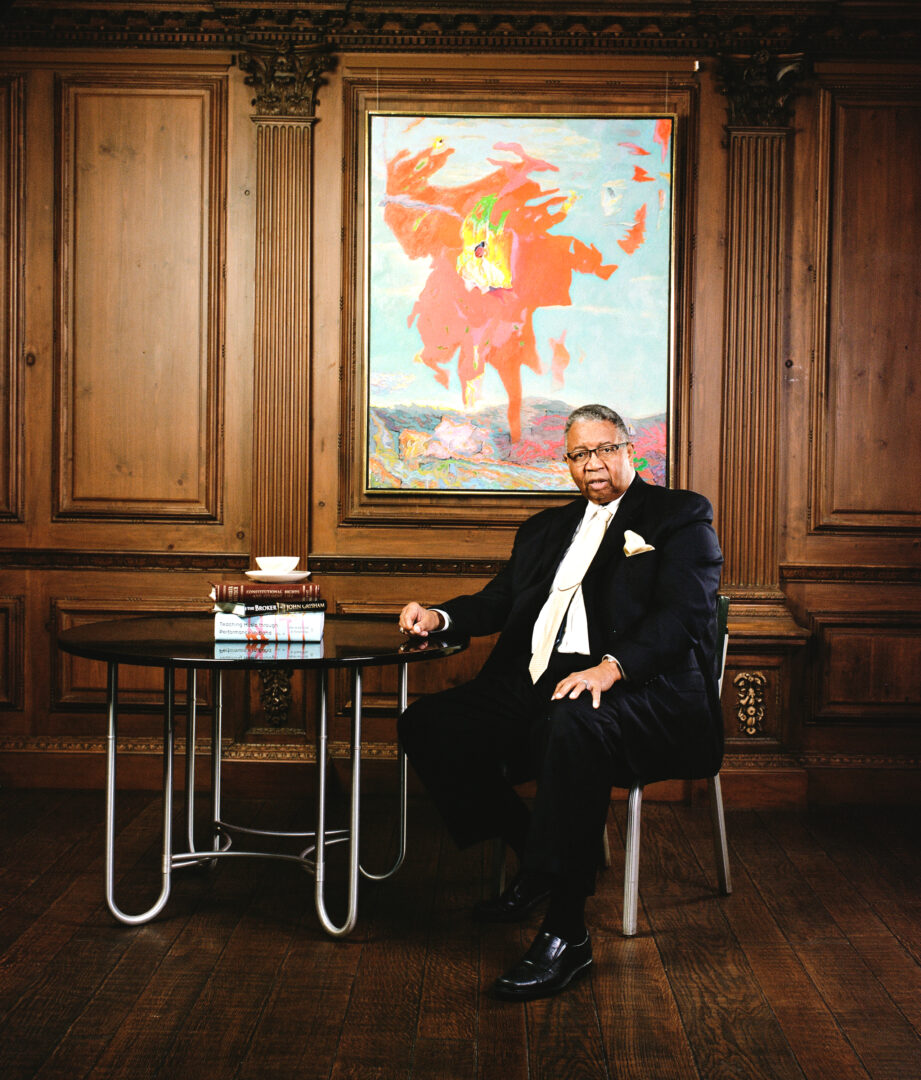

Gavin Benjamin (GB): Years ago, some members of the Museum came out to my studio in Pittsburgh. Eventually, the former Director/CEO, Anne Kraybill, offered me a project with the Museum. I saw it as a fabulous opportunity to create a completely new body of work. I wanted to create something longstanding to share with the community. Something that speaks about legacy, that tells the average person, I belong on these walls. I see me here. I was here. I see someone like me on these walls. And I belong. This sense of belonging has always been a part of me since I was a child. I remember thinking the first time my friends and I drove through Westmoreland County on a visit to the Museum: how do folks of color survive in communities like Greensburg around America? As an artist, a black man, an immigrant, and a gay man, I can count the ways I don’t belong.

Jeremiah William McCarthy (JWM): Thinking about site, talk to us about what it was like shooting at the Museum.

GB: It was an absolute honor to create this body of work within the space of the Museum. Museums can be magical places for people to dream. Douglas Evans, the Museum’s Director of Collections and Exhibition Management, took me into storage, the bowels of the ship, and I started to understand how the many pieces in the collection are connected. I’m an art geek who loves fashion and design. This was like shopping in the Museum’s collections. It was priceless. It was the same feeling for me as shopping at Barneys on 17th Street in New York back in the day. Or seeing the Christmas windows along 5th Ave each year. These spaces are my design museums.

EN: So how did you get it all done?

GB: This is a very big project. It was a collaboration and involved working with a team of creative people to help craft my vision for these narratives. Pamela Cooper, a native of Greensburg, was my casting director and community liaison. Michael Olijnyk, the former director of the Mattress Factory, aided with designing the many different sets. Ben Brady created a visual language for the behind-the-scenes, black-and-white shots. I think they have a rock and roll vibe. Emmy-award winning documentary filmmaker Nick Childers made the documentary. And Nina Friedman, my project manager, managed to keep the train on the tracks.

JWM: I know you approach things in a very organized, very methodical way, with no time for nonsense. Did anything surprise you during this project?

GB: I was surprised by how embracing and welcoming the Westmoreland community was to this project. I realized early on as we were casting what impact this project might have on people’s lives, and the Museum came to see that, too. For many people within the community this is a way to be seen and heard. For some people I know, this would be the highlight of their life, to have their portrait hang in a museum. We as artists have the power to tell meaningful stories, engaging difficult narratives. Museums just have to be open to the world.

EN: If you did this over, what would you change?

GB: I believe that each situation requires a different approach. Some of the things that were right for this project in Greensburg may not work for another city. One has to read the room and adjust, my mother would always say.

JWM: What is it that these photos accomplish that words cannot convey?

GB: Community and love are the words that describe what these photos accomplish. I believe we will be seeing and hearing about this project for a long time to come. I don’t want to underestimate the reach and potential impact projects like this might have on communities like Greensburg. I remember a white friend, who grew up in Greensburg, said to me, “Are there really people of color in Greensburg?” I hope this project answers that question.

EN: You’re drawn to the fabulous. When did that begin?

GB: As a child I spent a lot of time entertaining myself. Growing up in Brooklyn, my grandparents’ apartment was by Grand Army Plaza, across the street from the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Central Library of the Brooklyn Public Library. When most kids were outside playing, I was walking the gardens, looking around the museum, or borrowing books from the library. I was always curious, and the adults around me were busy with life, so they were just happy I was staying out of trouble. My family are immigrants from Guyana, once a British colony, who came to America in the 1970’s. Life really changed once I started school in America. Kids right away let you know that you are an outsider. Museums, gardens, and libraries have always been the “safe” places. They are where you can dream and rest.

JWM: Who are your influences?

GB: The short answer is there are so many and they are constantly evolving. After graduating from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, I went off to work for agencies that represented photographers, directors, stylists, hair and make-up artists, etc. There I learned how to produce photo shoots for artists the agency represented. Some of those projects involved magazine clients, advertising and editorial. My influences at that point were based on the commercial side of the arts. These photographers, illustrators, and directors are working artists. I learned from them the craft and skill to produce projects on a grand scale, and how to stay on budget! I also learned how to keep up. Most of the time there were three to six projects going on at the same time. Eventually, I became a freelance photo editor working for magazines. Then I was the one hiring the same photographers and artists who I once worked for as a producer, the same people who taught me. It was amazing to close that circle of influence. I could elevate their work and use it to tell stories.

EN: The title of this project references Nina Simone—why her, and why this song?

GB: We were coming off of the pandemic and I was spending

a lot of time listening to Nina Simone, Ella, Louis, the Cole Porter songbooks, The Specials, Moby, and Massive Attack. It was also a dark time for me internally. Although I was incredibly grateful that I could still get into my studio, I was also mostly alone in Pittsburgh, so I focused on pushing my work and staying busy. Every time I heard Nina’s voice and those words, Break Down and Let It All Out, there was this knife cut.

I had to find a way to turn the visceral pain and anger of this song into something positive. Also, I was thinking about Nina’s role in the civil rights movement.

JWM: What’s the first thing you would tell someone picking up a camera for the first time?

GB: For starters, I would immediately take away their digital camera and give them a film camera with 36 exposures and tell them to go have fun. Make some pictures and come back. If they have only 36 images, and they want to make them count, film changes the how, what, why. What is worth capturing? That’s what I’m thinking when I’m photographing with film.

EN: How has photography changed you?

GB: Maybe ironically, photography has allowed me to see the world in shades of gray and not just black and white.

JWM: Describe to us your favorite photograph.

GB: To tell you the truth, there are just so many kinds. I want to say the hand of Miles Davis shot by Irving Penn. And his still lifes and collaborations with designers like Issey Miyake. My favorites are timeless.

EN: What might people take away from this project?

GB: Back in the day, as the story goes, information was passed down from village elders to children. This is my way of having that conversation and providing a visual narrative to help advance this conversation. What do we carry forward and what do we leave behind? American history is being rewritten today by people who are afraid to have the real conversation of what it is like for a man of color to live in America today. This is my way recontextualizing history and writing these missing pages and passages from our history.

JWM: And end this for us with a song lyric . . .

GB: Birds flying high, you know how I feel . . .