Rip Van Winkle Returns!

After being absent from The Westmoreland’s 19th Century Gallery for almost a year due to its frame undergoing an extensive conservation treatment, visitor favorite Rip Van Winkle by George Frederick Bensell (1837–1879) has returned!

Welcome Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle back with a visit to the Museum and experience this wonderful narrative painting in person. Open 10am-5pm, Wednesday-Sunday. Please, register for your visit in advance!

But why did Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle leave the Museum for so long?

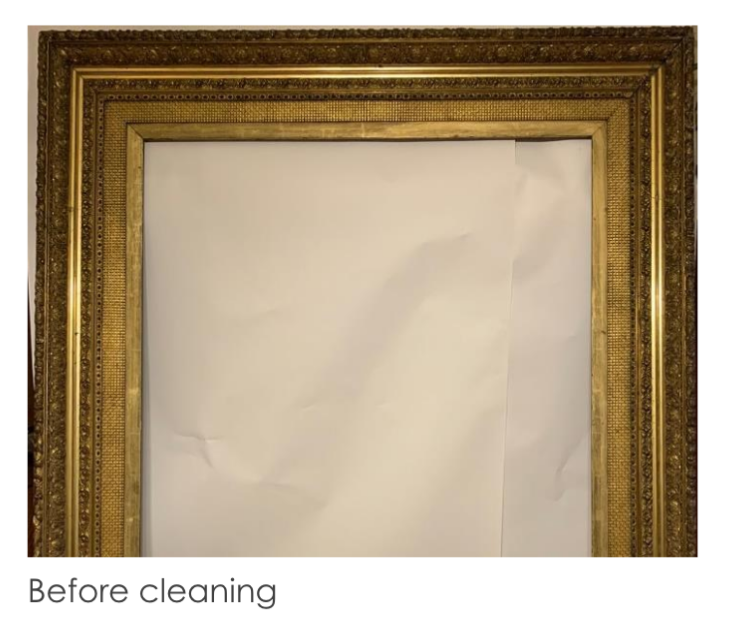

The narrative painting’s ornate frame, which has been on the piece as long it has been in the Museum’s collection since being acquired in 1977, was in very poor condition and in need of some care. To restore the frame, The Westmoreland worked with a conservator who thoroughly assessed the frame and its condition before the conservation treatment.

Composed of three different components, including an outer decorative molding and two liners, the frame that holds Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle is rather complex. According the conservator’s assessment, these liners are not believed to be original to the outer molding. Most likely the two liners were added to the existing frame to (retrofit) accommodate the Rip Van Winkle painting, which if you have never viewed it is quite large at nearly 4 feet high by 3 1/3 feet wide. The middle liner shows a screen motif that was gilded and toned with a patina. The inner most liner is a silver leaf liner that has been coated with a tinted shellac. The smooth sections of the frame are actually metal leaf tinted varnish, possibly shellac, used to imitate gold leaf gilding.

The ornate gilded areas were originally rendered in a material commonly referred to as compo and made from chalk, resin, glue and linseed oil, pressed into molds and adhered to basic frames. These compo elements were then coated with a material made from fine ground chalk and rabbit skin glue (boiled-down rabbit skins, usually French!) called gesso. Several layers of gesso were added and sanded to create a stain smooth ground. A thin layer of fine clay, tinted black, and glue was applied on top of the final gesso layer.

The ornate gilded areas were originally rendered in a material commonly referred to as compo and made from chalk, resin, glue and linseed oil, pressed into molds and adhered to basic frames. These compo elements were then coated with a material made from fine ground chalk and rabbit skin glue (boiled-down rabbit skins, usually French!) called gesso. Several layers of gesso were added and sanded to create a stain smooth ground. A thin layer of fine clay, tinted black, and glue was applied on top of the final gesso layer.

The conservator noted the choice of black bole was unusual for gold leafing but added that it gave a specific tone to the finish. Gold leaf was then applied on the decorative elements, burnished and a dark patina applied to increase the contrast in the elements.

The conservator’s review revealed a significant layer of grime on the entire frame, the grain of wood showing through the silver leaf, an unevenly applied coating on top of the leaf, old paint that had discolored with time, and several areas showed loss of decorative elements.

Conservation Frame Treatment

To return the frame to its former glory, it underwent an extensive conservation treatment. The entire frame was cleaned, removing the dust, grime, and overpaint. The unevenly applied patina was adjusted after the initial cleaning. Missing elements were reproduced, attached in the areas of loss, and were then gilded and toned to match their surroundings.

The losses on the corner of the smooth element had been overpainted with a material that had dramatically discolored. To remedy this, the overpaint was removed as much as possible while maintaining the integrity. The losses were filled with traditional gesso coated with a black bole and gilded. The original gilding was a silver leaf coated with shellac. Due to the level of damage and lack of uniformity of the surface, the inner liner was regilded and coated with a patina, enabling that section to be less of a distraction to the general balance of the frame design. To even out the overall sheen of the frame, a thin layer of synthetic varnish was used to coat the entire surface, producing a subtly gorgeous frame that now complements Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle.

To even out the overall sheen of the frame, a thin layer of synthetic varnish was used to coat the entire surface, producing a subtly gorgeous frame that now complements Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle.

Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle

Bensell’s painting Rip Van Winkle demonstrates his skill at combining a detailed landscape painting with a narrative portrait, recreating Washington Irving’s timeless tale.

Not familiar with Irving’s short story Rip Van Winkle? According to legend, Rip lived in a small village in New York State at the foot of the Catskill Mountains. He was a friendly fellow, but a rather lazy husband. One day to escape his chores and his wife’s nagging, he decided to go hunting with his dog, Wolf.

While climbing up the mountain, he stumbles upon a rather peculiar little man carrying a heavy keg, which he offers to help him carry. Rip and the man carry the keg deep into the woods until they meet a group of odd-looking men playing a game of nine-pins. To thank him for his help, the men invite him to quench his thirst with the mysterious liquid from the keg. After consuming one too many drinks, Rip falls into a deep, deep slumber.

Rip wakes up, thinking he has only slept for one night, but after gazing about he realizes he’s been sleeping for 20 years! He hurries down the mountain to his village, which is quite changed. The image of King George III on the sign over the inn has been replace by George Washington, indicating to the reader that Rip slept through the Revolutionary War. The story ends on a happy note though with Rip being reunited with his adult children and grandchildren.

The narrative painting captures Rip’s bewildered awakening after being asleep for 20 years. The artist clearly depicts the shock on Van Winkles face with a forehead creased in consternation and concerned eyes and realistically renders details of Rip’s appearance with a long white beard, balding head, ragged clothes, a rotted gun, and long sharp fingernails. Setting the life-size figure of Rip at the center and forefront of the mountainous landscape, Bensell focuses the viewer’s attention on the main character of the story.

Welcome Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle back with a visit to the Museum and experience this wonderful narrative painting in person. Open 10am-5pm, Wednesday-Sunday. Please, register for your visit in advance!

Bibliography

The text in the first two sections of this article, But why did Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle leave the Museum for so long? and Conservation Frame Treatment, includes excerpts from the conservator’s report that have been lightly edited by Director of Collections and Exhibition Management Doug Evans and Manager of Communications Maggie Geier.

The text in the last section, Bensell’s Rip Van Winkle, includes lightly edited excerpts from:

- Jones, Barbara L. “George Frederick Bensell (1837-1879), Rip Van Winkle, n.d..” Picturing America: Signature Works from the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, by Barbara L. Jones et al., Westmoreland Museum of American Art, 2010, p. 63.