Aaronel deRoy Gruber’s Alumascape III

Author: Brittany Reilly, Executive Director, The Irving & Aaronel deRoy Gruber Foundation

On the occasion of artist Aaronel deRoy Gruber’s kinetic outdoor sculpture Alumascape III joining The Westmoreland Museum of American Art’s permanent collection, and marking ten years since Art(ist)in Motion – the institution’s expansive 2013 exhibition covering the Pittsburgh modernist’s multidisciplinary trajectory – a reflection on (a facet of) deRoy Gruber’s prolific creative practice is particularly timely.

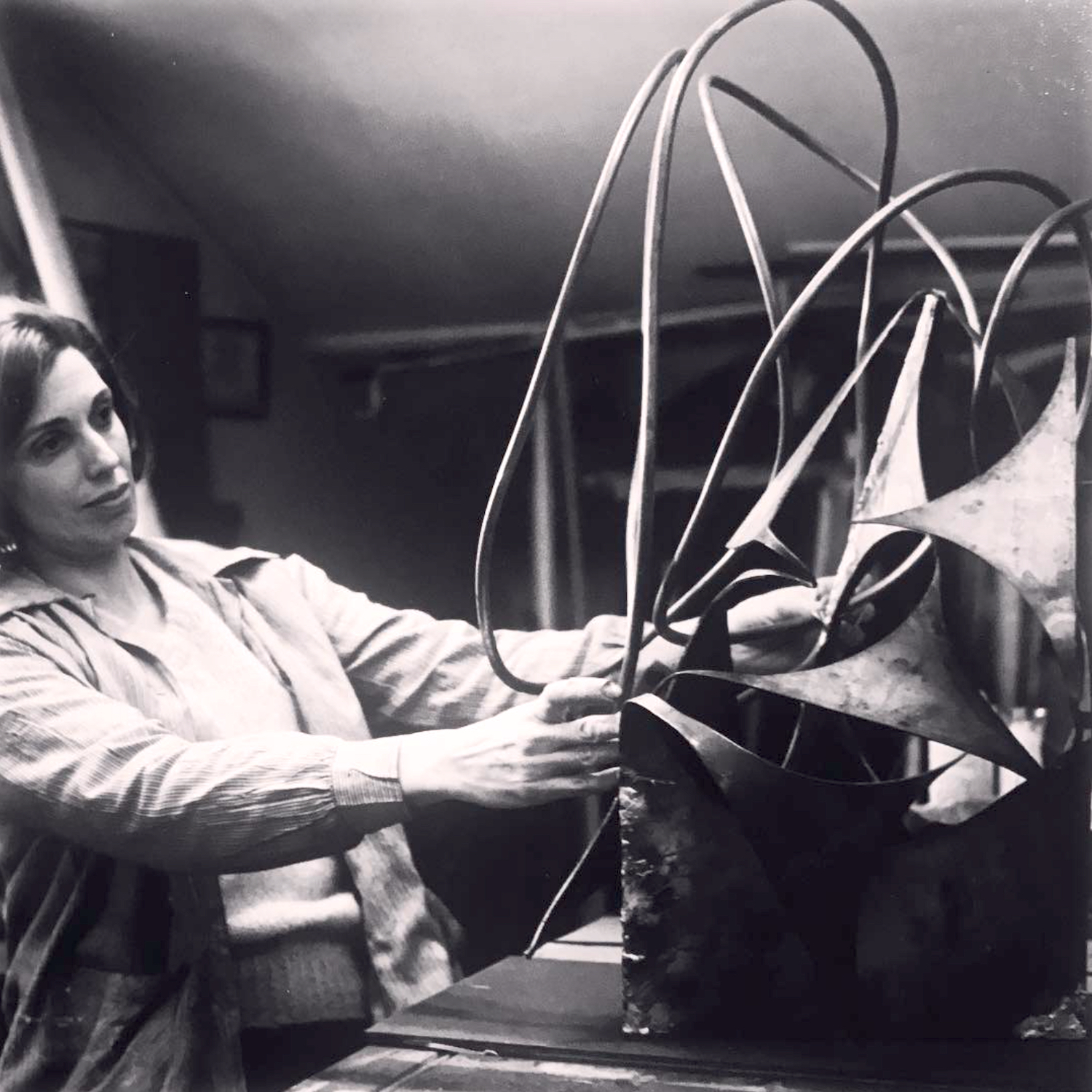

LEFT – Aaronel deRoy Gruber in her Pittsburgh studio circa 1960s. Photograph by Esther Kitzes. Aaronel deRoy Gruber Papers and Photographs, Detre Library and Archives, Senator John Heinz History Center.

RIGHT – Alumascape III photographed by Walt Seng, 1980. The Irving & Aaronel deRoy Gruber Foundation Archives. In 2022 the Foundation gifted Alumascape III to The Westmoreland in honor of Barbara L. Jones, Curator Emerita.

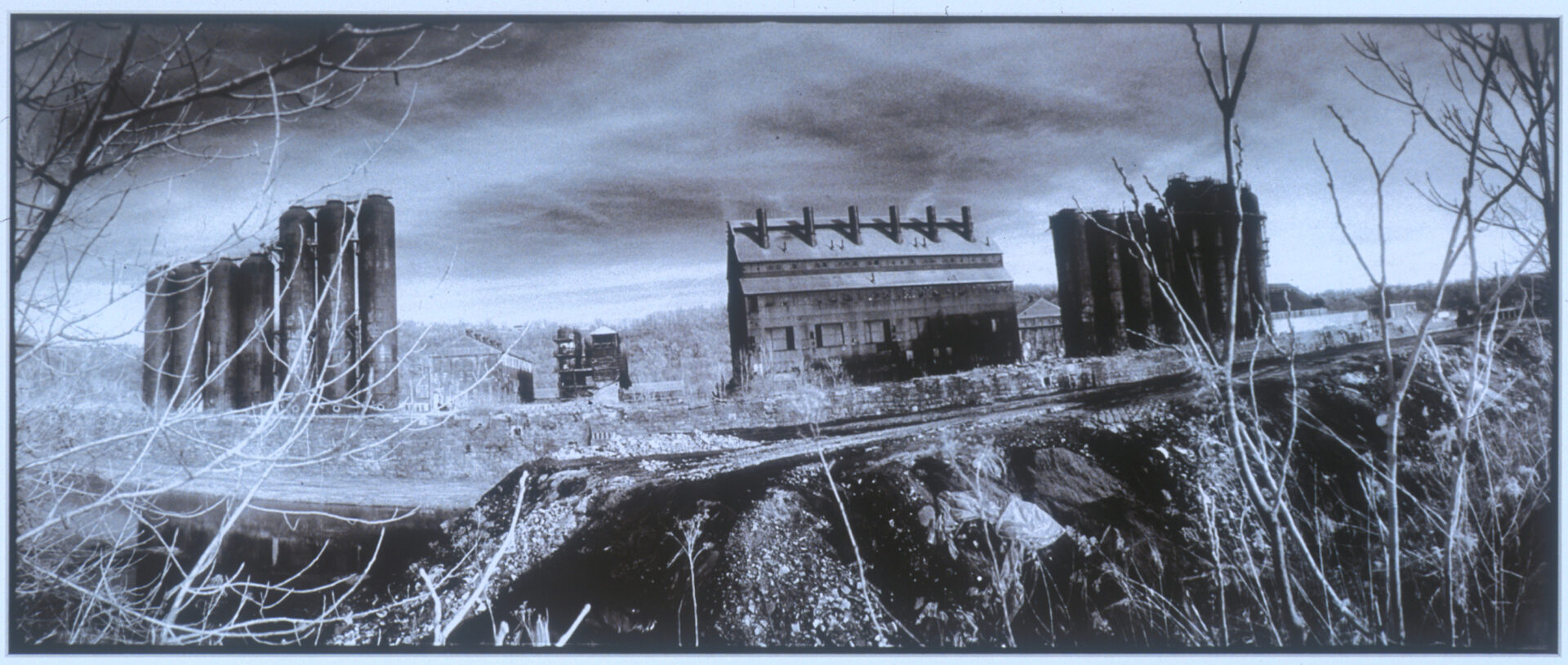

Alumascape III, an 8-foot abstract composition completed in 1980, complements the museum’s existing range of deRoy Gruber works: twelve black & white/silver gelatin photographs of former steel and industrial sites throughout the region captured during the 1990s in a state of desuetude, and four abstract sculptures completed during the 1970s when the artist employed sophisticated fabrication techniques in her studio and at specialty facilities, having sourced manufactured materials to artistically manipulate. One collection sculpture, Plexi Steel Turning, is especially remarkable in that it combines, as the title would indicate, stainless steel with a translucent Plexiglas surround, continuously rotating 360 degrees by way of a motorized base.

LEFT – Aaronel deRoy Gruber, Plexi Steel Turning, 1970s, The Westmoreland Museum of American Art.

RIGHT – Aaronel deRoy Gruber, Alumascape III. Courtesy of the Irving & Aaronel deRoy Gruber Foundation.

Comprised of six aluminum elliptical forms welded together along their interior edges and perched upon an elongated cylindrical base, Alumascape III rotates freely, set into occasional and intermittent motion by atmospheric wind and assisted by the oblique ovals and angled position of the sculpture’s uppermost portion. Tracing yet another oval in the airspace just above it, the composition transforms instantly in one’s presence and is further influenced by the orientation of the spectator. A departure from the control and consistency of her electricity-reliant motorized sculptures throughout the 1970s, Alumascape is a clever reminder of deRoy Gruber’s intrigue with and mindfulness of the human body and elemental factors.

In addition to wind, the allowance of natural elements to influence the surface of select industrial materials (raw aluminum anodizing or COR-TEN Steel gaining a desired rust layer) is a marker of time and reinforces deRoy Gruber’s interest in the unhurried metamorphic possibilities of an outdoor sculpture, as well as the immediate.

Born and raised in Pittsburgh and eager to interface engineered technologies with visual art experiences, deRoy Gruber was influenced by and immersed in regional industry and related mechanics both literally and conceptually.

After studying at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University) until 1940, deRoy Gruber (1918-2011) pursued her strong artistic inclinations first through abstract expressionist paintings and collages into the 1950s. Following a 1961 juried exhibition in Pittsburgh when deRoy Gruber’s entry was recognized by renowned modernist sculptor David Smith, the two developed a rapport, with Smith (who worked primarily in steel and pursued pioneering work in applications of welding and blacksmithing in sculpture) encouraging deRoy Gruber to explore the material and dimensional form prompted by the vigor and volume expressed in her paintings.

Nuances always present in deRoy Gruber’s sculptural work maintain an inventive contrast to the materials she chose. Throughout the artist’s practice she introduced curves in scenarios that commonly relied on hard angles, embraced the interplay of translucent and reflective surfaces with materials that weren’t developed to be captivating, sculpted portals through material valued for its opacity, and achieved an alluring lightness of form where weight is usually but a practical matter.

deRoy Gruber’s work in the manner of Alumascape III is comparable to the work of her peer, American sculptor George Rickey (1907-2002), who deRoy Gruber exhibited alongside at the World Expo of 1988, ‘Leisure in the Age of Technology,’ hosted by the city of Brisbane, Australia. At EXPO ’88 deRoy Gruber represented the United States, exhibiting Alumascape III alongside Rickey’s 1974 stainless steel kinetic sculpture, Two Planes Vertical Horizontal IV. This was one of many international exhibitions deRoy Gruber had participated in during the second half of the 20th century, albeit typically as one of very few female artists.

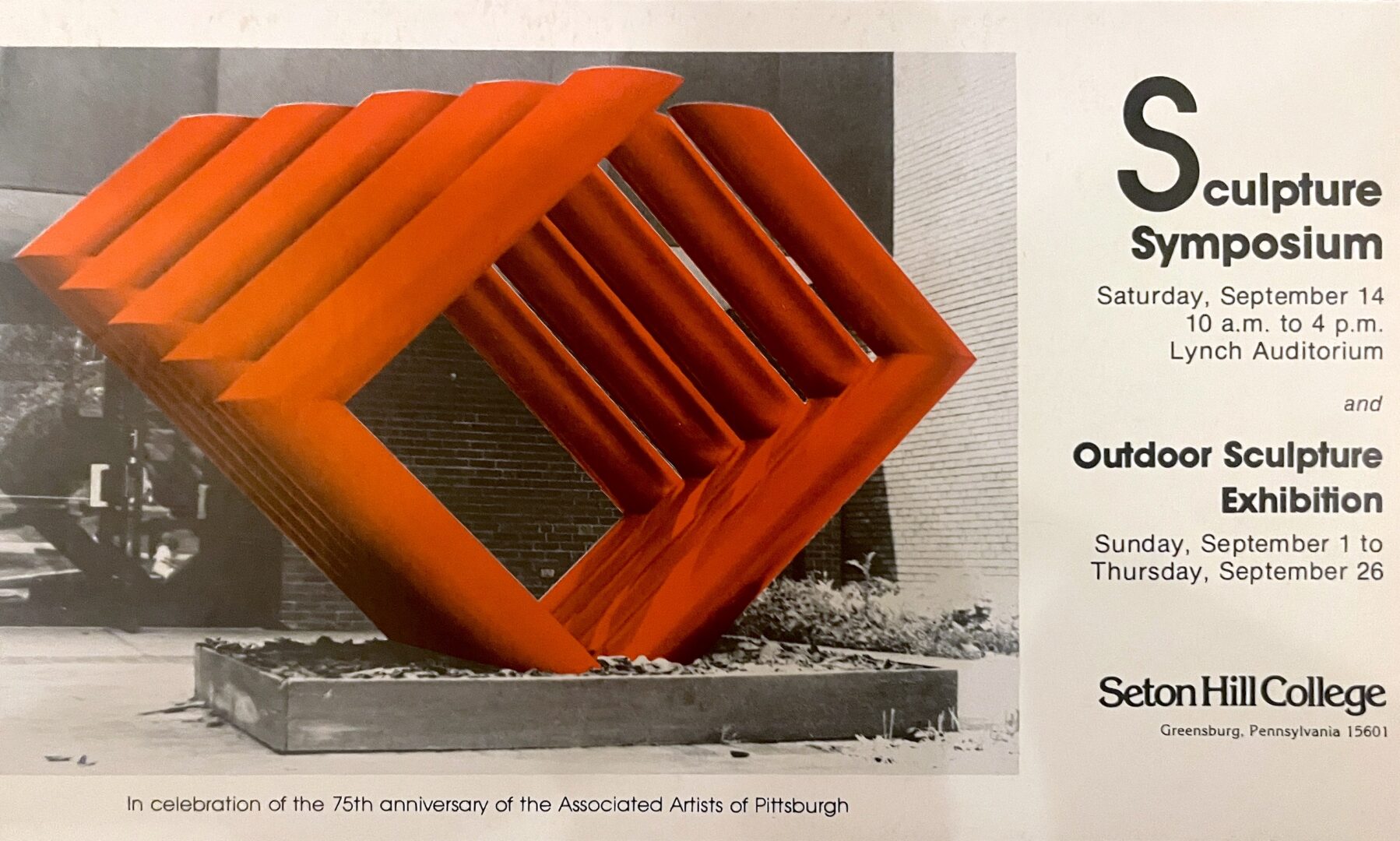

Back in Pennsylvania, Westmoreland City-born artist Sister Josefa Filkosky (1933-1999), student and later Art Department Chair and Professor of Art at Seton Hill College, Greensburg, summoned deRoy Gruber to participate in an outdoor sculpture symposium and invitational exhibition she had organized on campus in the Autumn of 1985. deRoy Gruber joined artists Douglas Pickering, Sylvester Damianos and James Myford along with speakers Dorothea Silverman, Marsha Moss and Virginia Watson Jones in a robust exchange between professional-academics and creators with interdisciplinary experience across architecture, visual art, design-fabrication and commission-based work for major regional corporations such as Pittsburgh Plate Glass, U.S. Steel and the Aluminum Company of America.

Filkosky and deRoy Gruber come together once again, this time on the grounds of The Westmoreland, for Filkosky’s 1965 Pipe Theme, an abstract composition of aluminum painted in potent hues of orange-red, situated at the garden entrance of the Museum. Often utilizing industrial tubing and portions of steel in her sizable outdoor pieces, Filkowsky’s Pipe Theme is no exception and offers a compelling correlation with deRoy Gruber’s approach.

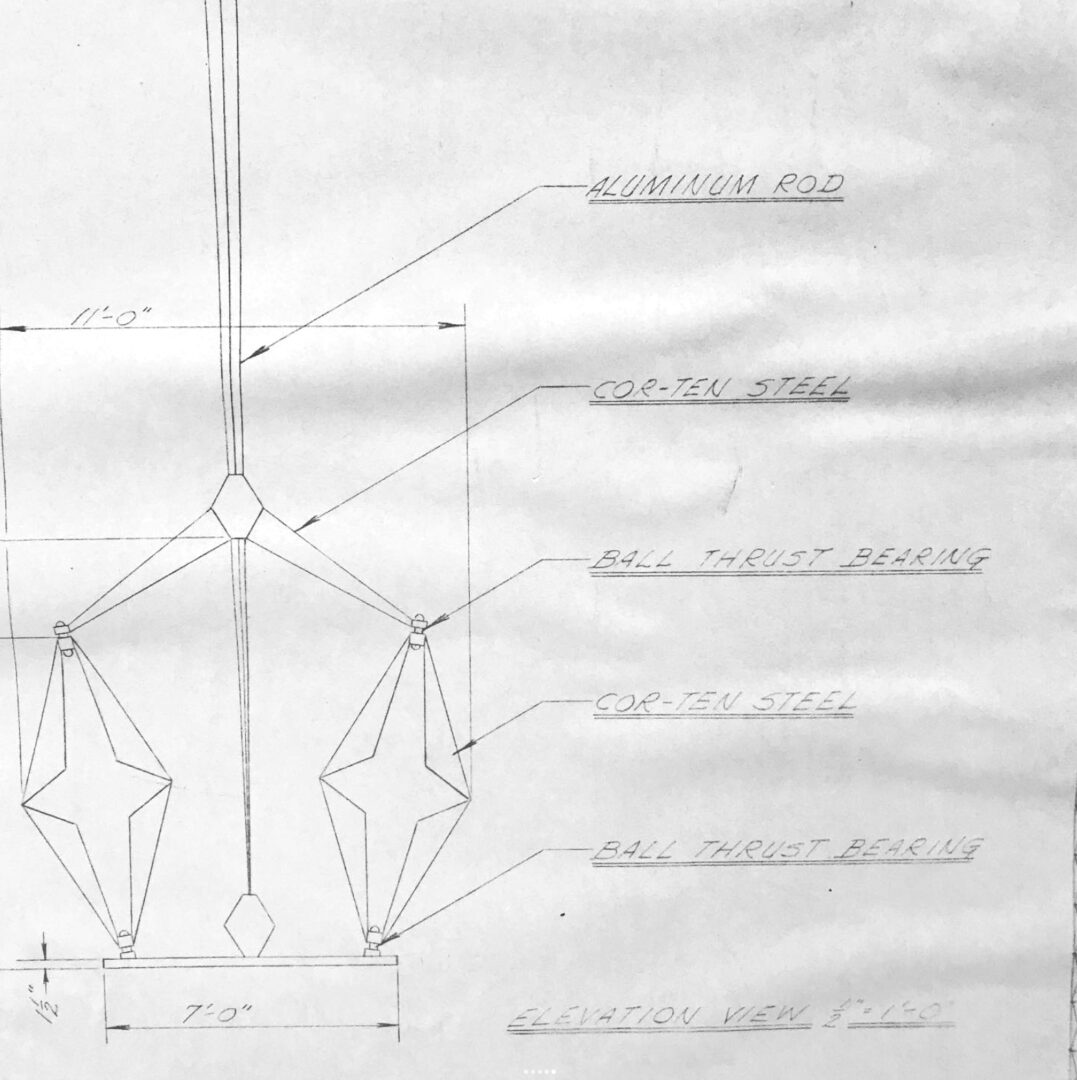

LEFT – Technical preparatory drawing for Windtower. The Irving & Aaronel deRoy Gruber Foundation Archives.

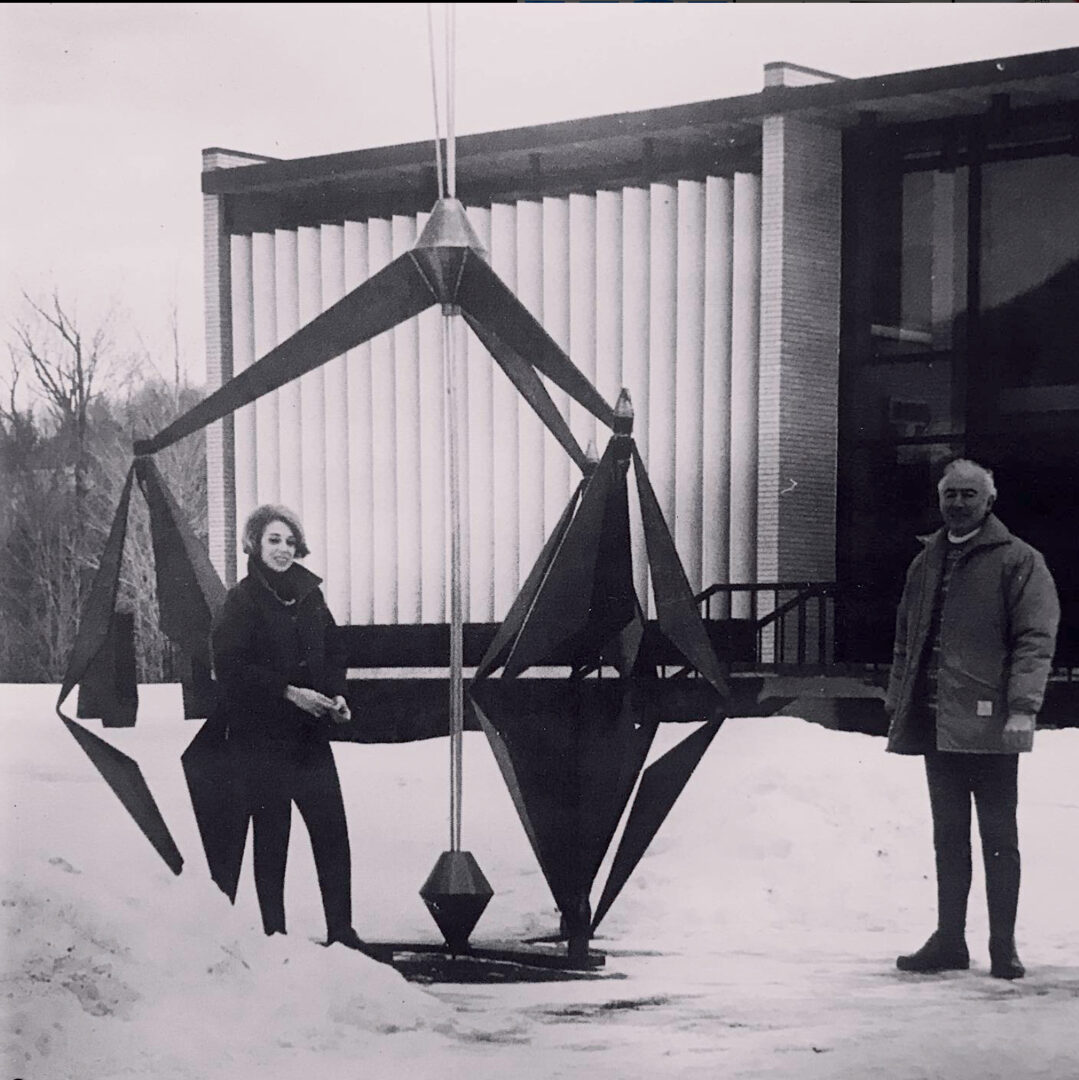

CENTER – Aaronel deRoy Gruber and her husband Irving Gruber standing near Windtower, 1969.

RIGHT – Artist maquette for Steelcityscape. Courtesy of the Irving & Aaronel deRoy Gruber Foundation.

The elliptical components of Alumascape III are slices from an aluminum pipe, a surplus material likely sourced from American Forge & Manufacturing Co. (later American Engineered Products Company), a facility on Nichol Avenue in McKees Rocks, Pittsburgh, co-owned by the artist’s family. Speciality ratchets, fittings, chains, bolts, hooks and cables were among the industrial products designed and manufactured by their engineers.

Public art held an important space in deRoy Gruber’s career and she worked both out of the studio and with American Forge facilities and engineers on occasions of large-scale works, some with kinetic mechanisms. Steelcityscape, one of her largest and most recognized public pieces crafted of solid stainless steel in 1976, has been sited in Pittsburgh’s Mellon Park since 2012 after being moved from its inaugural location within the portico of Hornbostel’s City-County building. Windtower is a kinetic arrangement of COR-TEN Steel that was first unveiled at the artist’s 1969 solo exhibition at Bundy Art Gallery and later installed on the plaza of the then IBM headquarters building at Gateway Center, Pittsburgh – the modernist facade a fitting backdrop for the diamond-like forms of her weathering sculpture.

Not at all immaculate, Alumascape III carries on its surface tangible evidence of the past, exhibiting subtle striation common in custom extruded metals and character defining dents and dings suggesting a previous application before it was adapted by the artist. deRoy Gruber’s later photography would explicitly capture once thriving, now fatigued, industrial enterprises. The artist saw these sites as resources for sculptural material and fabrication, returning to them a decade later to memorialize. Yet perhaps her most eloquent homage is expressed through works such as Alumascape III, with its tubular forms in a repetitive arrangement akin to smokestacks, and endless rotations one might associate with functional apparatus. While it transmits the past, the sculpture’s revolutions – without a beginning or end – bring us into the present moment, even inviting a contemplative state in which to imagine our time ahead.