—

Mingled Visions: The Photographs of Edward S. Curtis and Will Wilson

This spring, The Westmoreland features two exhibitions that explore the role of artists in creating and reinforcing stereotypes of Native Americans – Mingled Visions: The Photographs of Edward S. Curtis and Will Wilson and accompanying exhibition The Outsider’s Gaze.

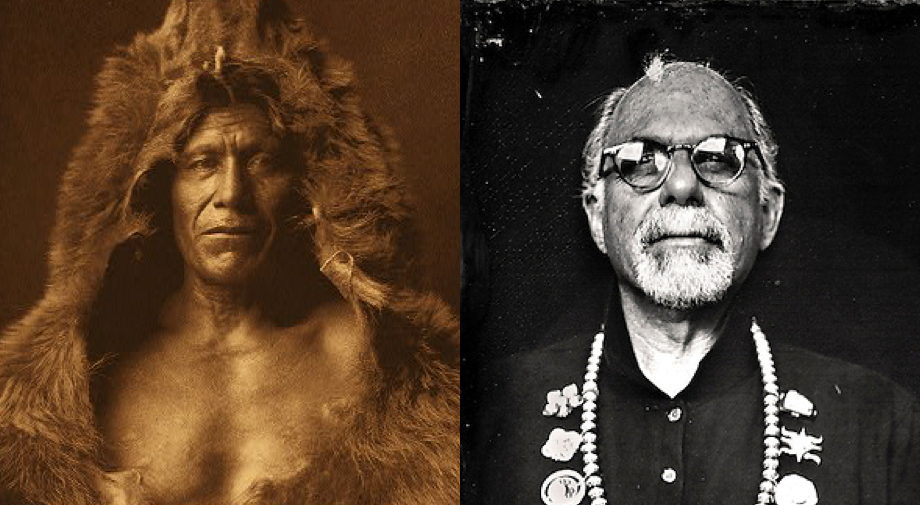

Mingled Visions: The Photographs of Edward S. Curtis and Will Wilson, pairs two photographers who share a vision to produce a permanent record of Native peoples. Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952), a European American, made it his life’s mission to create “a comprehensive record of all the important tribes in the United States and Alaska who still retained a considerable degree of their customs and traditions.” He accomplished this through years of arduous fieldwork, at great personal cost and hardship, with the publication of The North American Indian. This ambitious project, conducted from 1907 to 1930, resulted in 20 volumes of text and 723 photogravure prints that document over 80 tribes the photographer interacted with over the course of 32 years.

As evidenced in his extensive descriptions in each volume, Curtis closely studied customs, legends, folklore, traditions, music, home life, belief systems, and sacred ceremonies. He recorded them in pictures and sound, making between 40,000 and 50,000 photographs and 10,000 wax recordings, as well as film in the field, so that North American Indian culture would be preserved for the future. He felt an urgency to do this, because by the time that he began his project, all of the tribes that he photographed had already been forcibly removed from their land and were living on reservations. He feared that they were destined to be assimilated into European American culture and truly believed he was documenting a “vanishing race.”

Interview with Will Wilson

Complicating Curtis’ documentary project was, of course, his outsider’s gaze. Through such editorial choices as how he posed the sitters and staged the shots, the props and (sometimes inaccurate) clothing he included, and the specific people and scenes he captured, Curtis imposed his own, European American perspective of how Native Americans should be seen, not as they were in reality. The title “vanishing race” also signals a static culture, where Native Americans are fixed in the past. This is directly challenged by Will Wilson, a Diné photographer, who initiated the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) in 2012. The Westmoreland’s Public Programs Coordinator Mona Wiley spoke with Will Wilson to learn more about his project and motivation for creating the series. Please see below for the interview transcript.

Mona Wiley: Can you provide an overview of the process of creating the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange Series (CIPX) and how it differs from Curtis’ work?

Will Wilson: One of the ways it differs is that the project isn’t actually just of Native Americans, but it’s by a Native American photographer. But the people—the subjects— don’t have to be native. So when I think about these images, I think they’re all indigenous images, because I make them. I framed it in relation to Curtis, because he’s always the elephant in room when it comes to images of Native Americans, just because his work was so prolific and well-known, and it’s enjoyed a sort of a revival since its rediscovery in the ’70s. And so, in a sense, it’s strategic. I evoke his name, because I know that institutions have these collections, and they want to show them, and then people have kind of gotten “woke.” They realize they can’t just show this stuff un-contextualized. I was also interested in doing portraiture and was interested in the historical process.

MW: For those who are not familiar with the historical tintypes process can you provide a little overview?

WW: Basically I’m making my own 8 x 10-inch negative, in my case on a black metal plate. You make your own emulsion, and it’s wet and gooey. You take the photograph, and then you’ve got to immediately develop it. So you have to have a dark room with you wherever you go. There’s something about the wet plate process that’s a little fickle. Kind of all this hovering and intervening, but there’s certain things about the process that are a little bit out of your control, and sometimes it’s magical, and sometimes it’s frustrating. It’s just cool to have a hands-on, handmade, do-it-yourself kind of photography that’s much slower in a digital age. I also get to share that process. That’s part of the project. I get to show people how photography used to be, and there’s something about that alchemy that’s pretty fascinating and kind of inspires me, when I get tired, to keep going. People just love to watch this magic happen. I mean, I really think it is magic. It’s totally chemical, but somehow people have figured out there’s magic, and you kind of put it in a box, and it’s really fun to share that with people.

MW: Curtis conducted these ethnographic surveys, but the images tend to romanticize the indigenous populations he was photographing. Can we talk a little bit about why that is problematic?

WW: I think the problematic aspect was that he was kind of fixing people in a time that wasn’t real. If anything, those images for me are a testament to the kind of resiliency of those people who were being photographed, because they’ve gone through some really intense times. I also think about that. I’m glad those images exist as a testament to the people who survived genocide basically. There’s something about the romance and the kind of nostalgic nature of the images. Conversely, when he went to photograph Osage, it was the summer in Oklahoma, and they were all vacationing in Colorado, because they were some of the richest people in the world because of their oil wells, but he didn’t want to photograph that reality.

MW: Curtis has been identified as staging these scenes in his photographs, and he provided props to his subjects to tell a story. How does that differ from your subjects being invited to bring their own props to tell their story?

WW: Hopefully this project is a little more open, and it’s really about people choosing how to represent themselves. I definitely don’t stage people. Most of my subjects are shot straight on. They’re kind of engaging the lens in a way that’s saying, “Here, this is who I am.”

MW: In an article in National Geographic, you said that you never got tired of this process. At that point you had created 2000+ images. Do you still experience that feeling?

WW: I do. One of the cool things is I get to bring people into my dark room. They get to watch this. So I’m really kind of amazed by the magic that happens, and then I get to feed off of other people’s excitement. It’s fascinating to watch people react to it, too. So the answer is yes. I still get totally jazzed.

The North American Indian Photogravures by Edward S. Curtis is a traveling exhibition organized by the Dubuque Museum of Art, Iowa.

Will Wilson’s photographs are courtesy of the artist.

The Outsiders Gaze is one in a series of American art exhibitions created through a multi-year, multi-institutional partnership formed by the Philadelphia Museum of Art as part of the Art Bridges + Terra Foundation initiative.

Support for both exhibitions has been provided by the Hillman Exhibition Fund of The Westmoreland Museum of American Art.

This project was completed in partnership with the Rivers of Steel Heritage Area. Funding was provided in part by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation, Environmental Stewardship Fund, administered by the Rivers of Steel Heritage Corp.