The Great Search: Art in a Time of Change, 1928-1945

by Jeremiah William McCarthy, Chief Curator

Phase two of this exciting exhibition opens December 14. Plan your visit.

From the first stirrings of a global economic depression to the end of World War II, artists grappled with what it meant to be American in a rapidly changing world. The greatest symbol of this artistic transformation was perhaps American Art Today, a monumental exhibition held at the 1939 New York World’s Fair comprised of 1,200 artworks across all styles. The show was the result of the most extensive competition between 20th century American artists that ever took place. More than eighty artist committees representing all regions of the continental United States juried over 25,000 entries to select the final checklist. The presentation offered quintessential examples of then-fully formed movements, such as regionalism, American scene painting, and surrealism, alongside nascent abstractions. It was the first time in the history of world’s fairs that artists had the final decision on what represented a nation’s creative expression. Organizer Holger Cahill, then-national director of the government-funded Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), summed up the variety of ideas on view as American art’s “search with many paths.”

The Great Search: Art in a Time of Change, 1928–1945 takes Cahill’s observation as its point of departure, demonstrating that no single individual or aesthetic defined American “modern” art. In this two-part exhibition, a multi-layered story is told in portraiture, scenes of rural and urban life, and powerful evocations of objects and historical events. Drawn primarily from The Westmoreland’s collection—many artworks seldom-seen, recently conserved, or acquired for this occasion—the exhibition is amplified by key loans. These vibrant and complex depictions provide fresh insight into a period of profound change in the United States and the competing visual forms that defined an unfolding American experience.

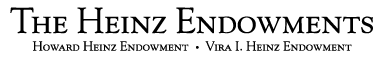

One of The Westmoreland’s best-known and best-loved paintings, Ernest Fiene’s Night Shift, Aliquippa (above), was included in Cahill’s presentation . It depicts a serpentine line of laborers as they enter a Jones & Laughlin steel mill during a pivotal moment in United States labor law. The previous year, the country passed the National Labor Relations Act allowing workers to unionize, and the year the work was painted, the Steel Workers Organizing Committee formed. While others chose to render similar scenes through a vocabulary of powerful formal elements and precise architectural lines, Fiene emphasized his hand facture and the human aspect of work—its repetitive and cyclical nature, as well as its illuminating, edifying aspects. He extends the line of men to the picture-plane positioning viewers themselves as the next logical extension in the assembly line.

Gift of Virginia Lewis

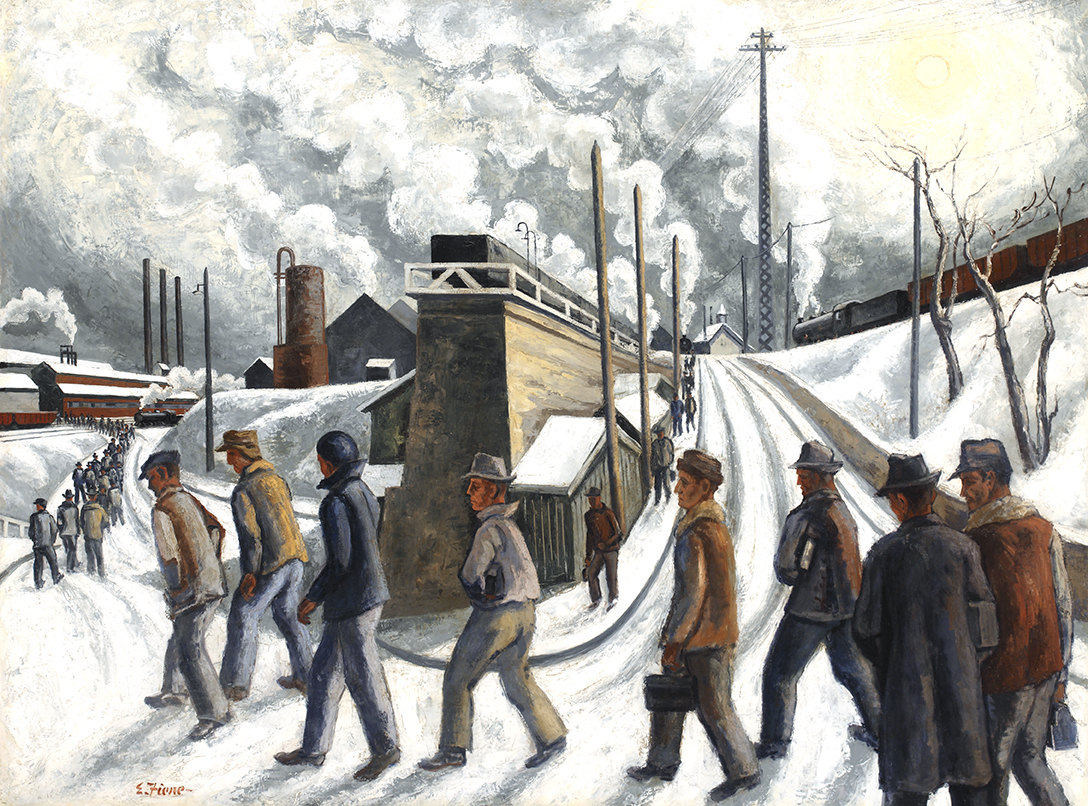

The picture was exhibited in the 24th annual exhibition of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh in 1934, where it was awarded the Carnegie Institute Prize of $250. It depicts the artist’s then-classmate at the University of Pittsburgh where both were pursuing graduate studies under Alexander Kostellow, whose masterful In a Park (above right), was newly conserved for the exhibition. Regarded by many as the founder of industrial arts education, Kostellow worked in 1934 to initiate the country’s first industrial design program.

One can see portraiture’s sparse distillation stretched to its limits by Andrew Wyeth. The commanding yet quotidian self-portrait (below) from the National Academy of Design—among Andrew Wyeth’s first mature paintings in the medium—is a master study in ambivalence. Does Wyeth’s searching gaze look through or past his viewer? Is the young artist’s expression one of determination or a register of trouble just ahead? Do the dry, wild grasses engulf his lone figure, or part for a pathway? And might the black hawks register his presence, or ours, from afar? The work seems to offer no answers, no pithy takeaways.

Gallery view of The Great Search, including Andrew Wyeth’s Self-Portrait, 1945, tempera on panel, 25 x 30, National Academy of Design, New York, ANA diploma presentation, February 5, 1945

Equally compelling is Isabel Bishop’s poignant Gina, a recent acquisition (below, left). Gina was exhibited in 1945 at the 119th Annual Exhibition of the National Academy of Design. Nearly a decade earlier, Bishop had won their prestigious Isaac N. Maynard prize in portraiture. A student of Kenneth Hayes Miller, Bishop struggled for years in her search for an aesthetic. There is a paradox on view with Gina that runs through all of Bishop’s works (nearly all of which involve the figure). The inwardly focused moments of life she chose to depict are the most evanescent and hard to sustain, yet paint is a timeless and static mode of address. How to represent life’s transient, transformative sensations, such as fleeting introspection, on a flat surface without flattening out the roundness of experience? Bishop’s answer was to look to art history, in this case, Rubens. Throughout much of her career, Bishop kept a piece of paper taped to her easel dotted with aphorisms that ended with a question: “Is it so?” This searching quality—a modest yet unyielding quest to discover what art can accomplish, how it affirms life, and what it can preserve of it—characterizes her best production.

Gift from Friends of the Museum

Bishop’s etchings also evinces the tenor of the times, as demonstrated by a suite of prints in the show: Girl Blowing Smoke Rings, Showing the Snapshot, and Noon Hour (above, right). These graphic works by Isabel Bishop are enlivened through precise gestures: a pair of interlocked arms, smoke billowing from pursed lips, and the point of an emphatic finger. More often than not, Bishop’s work depicts such intimate exchanges between young, female office workers—a social type achieving increased visibility as men left the workplace for war. Despite the widespread sentiment against women working outside the home in the first half of the twentieth century, women did enter the labor force in greater numbers over the interwar period, with participation rates reaching nearly 50 percent for single women by 1930.

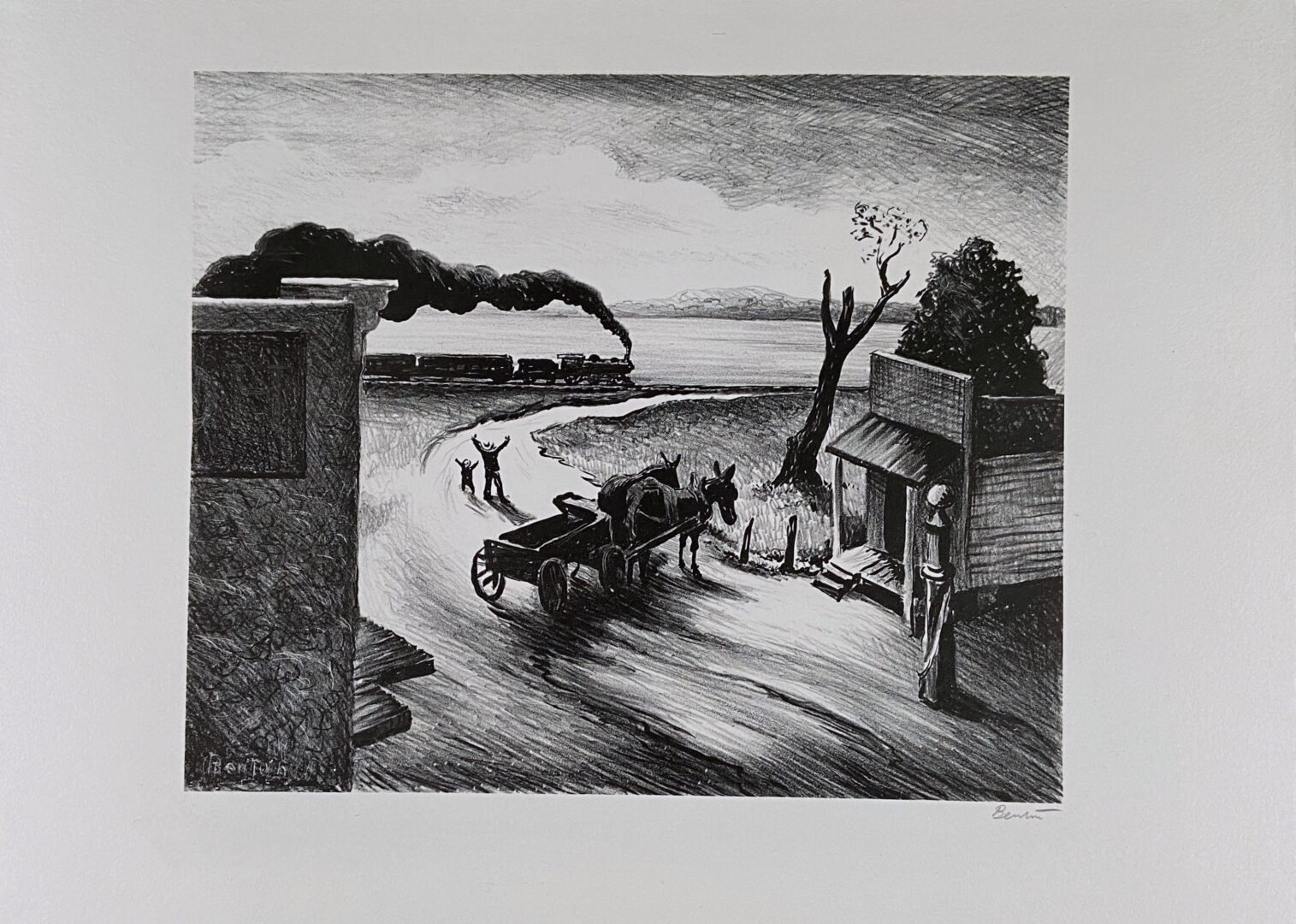

Expanding this time period’s familiar narrative beyond well-known names is an aim of the presentation. This is accomplished through an emphasis on artists of color, queer, and women artists. Paul Cadmus’s etching Stewart’s is an iconic image (above right). Stewart’s Cafeteria opened its doors in 1933 in New York City’s Greenwich Village and quickly became a popular downtown space for the queer community. The year after the print was made, the manager of Stewart’s was convicted of “operating a disorderly space.” A district attorney’s complaint cited that the cafeteria was “used as a rendezvous for perverts, degenerates, homosexuals and other evil-disposed persons.” Cadmus, in a witty move, features a patron going into the men’s room, glancing knowingly out at the viewer over his shoulder. Simultaneously revered and reviled by critics, he had achieved such notoriety in the United States by 1941 that Encyclopedia Britannica featured him (above right) alongside other artists in the exhibition—such as Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry—to illustrate “Famous American Painters.”

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, another artist whose work is part of The Great Search, also lived a double life, defining and redefining what makes an “American” artist. On the one hand, he was a leading modernist. He sat on some of the most prestigious art juries, and, in 1948, was the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art—the first ever granted to a living artist. On the other hand, his career was plagued by issues of nativist racism. During World War II, he was declared an “enemy alien,” his movements were restricted, and his camera was confiscated. He never became a citizen of the United States because of restrictive immigration laws.

Alongside the search for a formal aesthetic, there was also the question of content, and how to represent one’s community to its members, as well as to those outside it. In the late 1920s, Allan Randall Freelon began to summer in Gloucester, Massachusetts, a seaside New England artistic community. His landscapes from this period are luminous and impressionistic, for which he was criticized and labeled a traditionalist by many, including the writer and leading theorist of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain Locke. Despite this, Freelon frequently mentored others, inviting younger Black artists to Windy Crest, his summer residence in Telford, Pennsylvania. Freelon put no restrictions on the art he produced. His approach is in dialogue with an artist like Selma Burke, whose work will be on view in the second part of the exhibition (opening in mid-December).

During the period under discussion, American artists attempted to impose order on a world they perceived as increasingly spinning into chaos, whether through references to history, religion, or even faith in painting itself. Bradley Walker Tomlin’s To the Sea is one such example (below). In 1942—the year the work was painted—German submarines moved into American coastal waters. During the first months of the year, German U-boats sank more than 100 ships off the East Coast of North America, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea. It was a moment of general dread and one of the first times during the war in Europe when battle felt so palpably close to home for Americans. Tomlin viewed this painting as a record of his thoughts about the moment. While the influence of cubism provides unity to the picture plane, the work’s emotional content is unstable. Rather than a picture of a shipwreck, it pictures feeling shipwrecked.

American abstract painting flourished in the period between the Depression and World War II, and many of the artists in this exhibition participated in this transition. As one of the era’s famous maxims goes, artists are no longer “representing reality,” they are “making reality.” Alongside Tomlin’s approach is an artist like Arthur Dove, with his iconic Sunset (below). Here, Dove transforms a scene from his hometown in New York State by revealing the energy and essence of the natural phenomenon within the observable world. Dove—and others of his generation like Marsden Hartley and Milton Avery, on view in this exhibition—is a bit of an outlier in the grand narratives of American art history. The artists are often viewed as too “abstract” during the heyday of realistic art of social concern, and too wedded to objective experience during the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism. Yet all three have benefited in recent years from reassessments of their careers, demonstrating how their art embodied deep and complex connections to the world and how the stories of modern American art might be told otherwise.

Part one of the exhibition ends with a work as provocative today as when it was first painted: Franklin Watkins’s Suicide in Costume (below right). The painting is on view for the first time in over a quarter of a century following extensive conservation. In 1931, at the age of thirty-seven, Watkins was suddenly catapulted into the national spotlight when the painting won first prize at the prestigious Carnegie International (then-Pittsburgh Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture). The choice immediately polarized artists and critics—traditionalists detested its subject matter, avant-garde artists saw the win as a sign of modern progress, and for others, the choice seemed to signal the ascendancy of American art on the international stage. In interviews, Watkins relayed the story of the work’s creation. Dressed up to go to a New Year’s party, the artist received a phone call from a friend conveying the devastating news that a mutual friend had taken their own life. This juxtaposition of the beginning of a new year and the expiration of one set something off in Watkins that resulted in the deeply felt painting. Placed within the exhibition next to Edward Francis McCartan’s sumptuous and still enameled terra cotta Repose—both the dream and its nightmare—the juxtaposition feels almost reparative (below left).

Edward Francis McCartan, Repose, 1944, enameled terracotta, Gift of Dr. Michael L. Nieland

The Great Search: Art in a Time of Change, 1928–1945 is on view through September 2025 at The Westmoreland Museum of American Art, 221 N Main St., Greensburg, PA 15601, 724–837–1500, www.thewestmoreland.org. It is organized by Jeremiah William McCarthy, Chief Curator, The Westmoreland Museum of American Art.

This is one in a series of American art exhibitions created through a multi-year, multi-institutional partnership formed by the Philadelphia Museum of Art as part of the Art Bridges Cohort Program.

The exhibition is generously supported by The Heinz Endowments.